INTRODUCTION | DOCUMENTS | IMAGES | MAPS | EDITOR

|

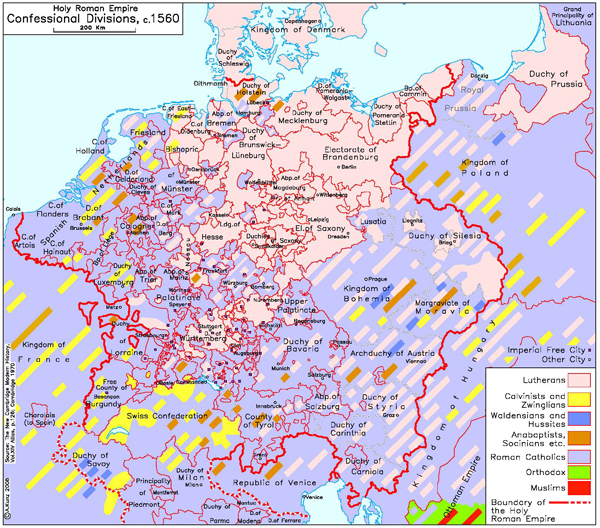

In the sixteenth century, the long-standing pressure for church reform acquired new force through the programs of reformers such as Martin Luther in the Saxon town of Wittenberg, Ulrich Zwingli in the Swiss city of Zürich, Jean Calvin in independent Geneva, and others. Fueled by a flood of pamphlets, polemics, and programs, their movements spread far and wide. The result was a set of schisms, through which various Protestant confessions emerged alongside the Catholic faith. In the Empire, the Lutheran confession, and later the Reformed (Calvinist) confession, spread under the protection of princes and urban magistrates, giving birth to territorial and urban Protestant churches. Some states, notably Bavaria, kept the new faith from spreading. At the Diet of Augsburg in 1530, Emperor Charles V tried and failed to save religious unity. More than two decades of sharp political and military confrontations followed. They culminated in the Schmalkaldic War of 1546/47 and were then put to provisional rest by the Religious Peace of Augsburg (1555). This agreement permitted princes and cities to tolerate the Lutheran confession (this right was extended to the Reformed confession in 1648). It also enabled princes to require their subjects to conform to the established religion or emigrate, a rule later dubbed “whose the rule, his the religion” [cuius regio, eius religio]. Toleration of more than one confession was established in a number of Imperial cities and also practiced locally in some territories. By special provisions, Catholic bishops were not allowed to expel dissenters, but bishops who converted to Protestantism were stripped of their offices. The map shows where the Reformation had been introduced by 1560. The most important areas lay in the Empire’s northern and central zones: Lutheranism in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, Brandenburg, Braunschweig-Lüneburg, Hesse, Saxony, and (though outside the Empire’s boundary) Prussia. In the south, Lutheranism was established in Württemberg, parts of Franconia, and numerous Imperial cities. After c. 1580, the Catholic Church experienced a massive revival, which halted the advance of Protestantism and even allowed the old faith to recover some episcopal territories and most of the Austrian lands and the kingdom of Bohemia. Catholicism remained predominant in the western and southwestern portions of the Empire, including most of Alsace and all of Lorraine, as well as Bavaria. The third, Reformed confession spread via Geneva to France, the Netherlands, and some of the German lands. The outcome was a religious geography which survived both the demographic shifts caused by both the Thirty Years War (1618-1648) and the Second World War. Please click on print version (below) for a PDF file with enhanced resolution. This file is best viewed at 200-300%.

IEG-Maps, Institute of European History, Mainz / © A. Kunz, 2007 |

print version

print version return to map list

return to map list previous map

previous map